Can We Be Friends?

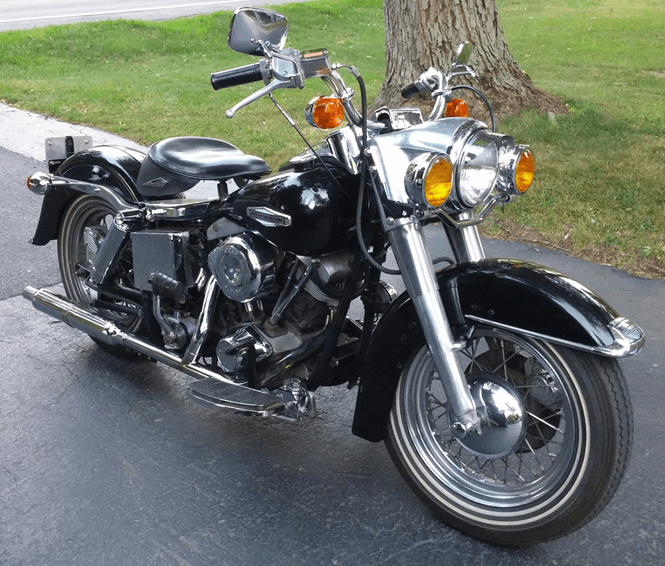

About three years ago (2016), I bought a 1974 FLH that looked pretty good, overall, but was obviously rough around the edges, to say the least. It terrified and intrigued me all at the same time. It was tough to ride – very mechanical and beasty – it wouldn’t hold idle, it had an exhaust leak, none of the dash lights worked. Turn signals? Nope. I think the only lights that worked on the bike were the headlight and brake light. There had been many hands on this bike over its lifetime, and they didn’t seem to be connected to brains – that was pretty obvious by the mess the bike was in.

I wanted to ride this bike, but it was pretty sketchy, and in the first few months I had it, it left two large puddles on my garage floor right under the front forks. So the bike pretty much sat in my garage. I would look at it, tell myself to sell it because I’d never get it running, then I’d not sell it because there was something about it that I – loved? Wanted? Needed?

Finally in September 2018, I decided to get the front forks done. I rode the bike out to Dan Thayer in Corfu, NY (Thayer Sales & Service). He got another bike of mine running great, so I asked him about my shovel. In a move that he possibly regrets, he told me to bring it on out to him.

So Dan did the forks for me, and I rode the beast home. On the way home, the right rear turn signal, which was mounted to the fender strut, loosened up and was hanging by its wire. Sigh. I wanted to put bags on the bike, and the rear signals were going to have to move anyway. As I started taking stock of just how much of the electrical on the bike did not work, it made sense to me to just rewire the bike.

As I stood in my garage, staring at this beast, with its drooping taillight mocking me, I decided that I was going to rewire it myself. Me. No mechanical experience whatsoever, beyond changing the fluids in my modern bikes, which I had just learned to do. Yeah, that me. But I also knew that if I wanted to ride this bike, or any old bike, I would need to know a whole lot more about bikes in general than just press a start button and go. Clearly what I lack in knowledge, I also lack in common sense.

I talked to a few people about it, including Dan Thayer, and I’m certain they all figured I’d start, give up, and either never ride the bike, or haul it to someone to finish. I have to admit, I had a little voice whispering the same thing in my ear. But I went for it. I really had nothing to lose, and everything to gain, because even if I totally screwed it up, I would learn something. Right?

So I found a used Harbor Freight lift on Craigslist and dragged it home. Some friends helped me get the bike up on it and strapped it down for me, and I started tearing the bike down. I wasn’t even sure how far I was going to have to go, but I ended up basically going right down to the frame. Instead of bagging and labeling the fasteners, most of the time, I just put them back where they came out of. I knew I’d never remember what my descriptions on the bags would mean later. This was the first of many times that I, or someone else, had to save me from myself.

One of my FaceBook posts from this time sums it up pretty well. “Venturing into the unknown, doing what seems like a huge project to me, hoping I don’t screw it up beyond repair, hoping I don’t open a larger can of worms… Step 3 in shovel rewire: Remove everything that covers a wire or contains one (or more). Repeat until there is nothing else left to remove.”

Once I got the bike pretty much stripped down, I degreased it (again) – a chore that seemed to repeat itself periodically because the frame and all the mechanicals were just caked with grease and dirt. I have degreased that bike probably 4-5 times, and I still find places that I missed.

When I exposed the main harness underneath the tanks, every single wire in the dang harness already had a splice in it – apparently a previous owner had rewired the bike once already, and did a cob job on it. No wonder nothing worked right. The further into this I got, the more it becomes obvious that I made the right call by doing a complete rewire.

At this point I was all in. There was no turning back. I was fully committed to this bike. I was terrified. But pretty proud of myself for even getting this far. And I was learning many things:

- How to read electrical schematics. Sort of.

- That you can’t reach that little nut waaay back there without taking something else off the bike, so don’t even try. OK, try, but stop before busted knuckles happen.

- That I still need more tools, even with the two tool boxes and pegboard full.

- That you need to wear two pairs of socks to keep your toes from freezing when it’s 25 degrees out.

- And, finally, that I needed a better heater in the garage.

But the biggest things I learned were that (A) I’m pretty lucky, and (B) I’m pretty dumb. In one of my weekend thrashes, I didn’t put the straps back on the bike. It was fine for a few days, but one day, I came home from the gym, and there was my bike – lolling on her side, looking sad.

The day before, I had just pulled all the trim off the fenders and sat them on the floor beside the bike. By some small miracle, the bike just missed smashing the tins when it fell.

I snapped a pic so I’d never forget to strap the bike again. Then I grabbed the frame and heaved her upright. But the bars were turned, the rear tire was right of center of the lift, and I was, well, stuck. Didn’t think that one through. So I can’t let go of the bike, and I can’t get it secured. I think, oh no, where is my phone? Cold sweat. Please, oh please! Let it be in my pocket where I can reach it. Fortunately, it was, so I start calling a couple friends – no answer. No answer. No answer. Feeling just a little desperate, I hit up my boss and he answered! He was about 5 minutes away, so I stood there in my freezing garage, holding the bike till he got there. In about 2 minutes, he had it straight on the lift, and we strapped it down. Lesson learned. Very thankful to be as lucky about that as I was.

Bonus: I think I set a new deadlift PR (personal record) as well.

At that point, the tenor of my relationship with this bike had been set. The bike would allow me to get something right every once in a while with relative ease. Then it would give me the giant middle finger, and I’d have to wrestle it to the mat to get one little thing accomplished. Other times, I would simply screw myself, unwittingly. And so it goes.

Well written. My R1 chose to throw itself off the bikelift and landed on a tiny kids plastic scooter which saved the R1 from damage……..amazing!!!

LikeLike